|

Title | Social Influence of Gender |

| Author | Sean Harte | |

| Key Concepts | Oppression, Anti-oppressive Practice, Sexism, Psychology |

|

Essay |

|

“Drawing on your understanding of social influence discuss the overt and covert ways in which gender-based behaviour is learnt and reinforced in British Society. What are the implications of your discussion for your professional practice?”

Source:

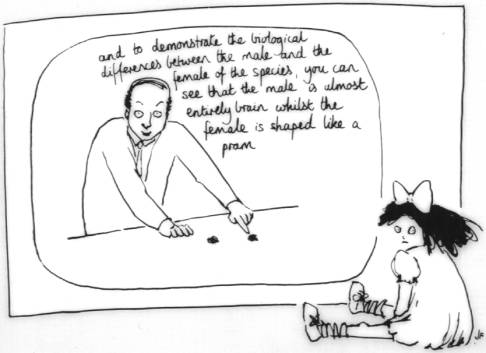

Siann, cover

illustration (1994) Introduction This essay will discuss some of the ways in which gender based behaviour is learnt within British society. We will begin with an exploration of what we understand by gender and how this may differ from the purely biological categorisation of sex. Next we will discuss some of the ways in which gender-based behaviour and activities are learned and reinforced within patriarchal British society, with particular descriptions of how gender roles are prescribed within work and education. We will see through these descriptions of how gender based norms are described that it is difficult to separate overt and open influences from those which are covert, hidden and secretive. We will discuss the implications these norms and expectations place on individuals and will debate how these impinge on the psychological development of a self-identity, especially for those individuals who do not easily fit into the mould which these norms have created. Lastly we will look to youth work and what role it may play in lessening the impact of these social norms and stereotypes and consider how this may be achieved. Thus we will conclude with an alternative model of understanding for gender, which may be used, within our practice, to help individuals explore their selves and their feelings, their beliefs and their understandings, and self-actualise towards the person they can be and want to be. Indeed this model would be of great benefit to many individuals if it were adopted by society as a whole, rather than being limited to the confines of the practice of the youth and community worker. Gender

- a Sociological Construct Geneticists have discovered in the last decade or so `that the genetic difference in DNA between men and women amounts to just over three percent` (Bly, 1990: 234). Is this three percent then the only factor to account for the vastly different roles and behaviours of women and men in British society? Social science brings us another explanation for the societal differences between men and women, the concept of socialisation process. In order to explore this potential explanation it is required that we accept that the concept of gender can be distinctly differentiated from the biological classification of sex. The distinction between `sex` and `gender` made popular in Britain by Ann Oakley (Oakley, 1972; 1981; 1985), although challenged as `problematic` by certain authors (Hood-Williams, 1996), is widely held within the social sciences as a classification of difference. Oakley differentiates between sex as referring to biological categories of male and female, whilst gender refers to human traits linked by culture to each sex, masculine and feminine. `The nature of sociological discussion on gender has been transformed by the impact of feminism and women’s studies’ (Abercrombie, Warde, et al, 1994). Indeed, Abbott and Wallace use feminist perspectives to argue that gender divisions are `socially constructed` and to challenge the male patriarchal ideology which originated these theories, arguing that it is `partial and distorting` (Abbot and Wallace, 1990). Abbott and Wallace identify four feminist sociological perspectives, liberal/reformist, Marxist, radical and socialist, that although differing in their opinions of cause, all argue that women are oppressed in British society and thus that men and women receive different and unequal treatment from society. Learning

Gender in British Society It can prove difficult to separate the differing attributes of male and female into categories of purely biological and sociological influence. This is due to the sociological influence of others being present from birth. Indeed from birth, reactions and gestures towards an individual are practised according to knowledge of the sex of that individual. As Siann describes `Despite the fact that there is no evidence to suggest sex differences in psychological attributes during the first years, studies have shown that babies are interacted with in different ways depending on the sex they are thought to be` (Siann, 1994: 78). Many studies, despite some methodological problems, appear to conclude that, there is evidence that parents handle their sons and daughters in different ways, for example offering toys to same sex children, and cuddling to stimulate opposite sex children (Lewis, 1986). Similarly other studies suggest that young children themselves interact differently with mothers and fathers for play and in times of stress (Spelke et al. 1973), as well as girls being more likely to initiate interaction with adults (Ross and Goldman, 1977). We can see then that gender is both `taught` and `learnt` from a very early age. This learning or conditioning, continues through an individuals life, indeed it is difficult to think of any facet of life in British society in which gender roles are not reinforced. In the field of employment we see vast inequalities in pay and the distribution of labour towards men and women, much of which is based on the supposition that men make more reliable workers, as they will not become pregnant and/or take family priorities over their work. Although it is true that men, at least for now, will not become pregnant, they are perfectly capable of prioritising their family commitments over their work in a similar way to women. However the gender stereotype of masculinity sees the male as a detached and unemotional worker drone, providing for the family in a mainly financial role. As Harris describes it `Through the exchange of labor men earn money that allows them to take care of their needs`. Harris goes on to quote an unacknowledged craftsman as declaring `The messages I received from my environment were that men were only important as providers, that work came first, and work was where one’s true identity as a man came out and was judged` (Harris, 1995: 73). In education, there has been a steady and progressive shift in the academic achievements of females, which has seen the gender gap in schools not only closed, but girls have overtaken boys; while in higher education the gender gap is closing steadily (Abercrombie and Warde et al., 1994: 233). However gender influence can still be seen in effect as `Women are more likely to gain arts and domestic science qualifications, while men are more likely to gain scientific and technical ones` (Abercrombie and Warde et al., ibid.). Perhaps this may not be overly problematic, but for the addition of values placed on these qualifications and the employment routes to which they lead. For example, the caring professions such as nursing, care assistance, and our own community and youth work roles have historically be seen as predominantly the domain of females. This is not in itself a problem, however the work is also historically low paid and seen as women’s work, hence a man attempting to forge a career in these fields is often challenged as to his masculinity, or indeed his sexuality. Gender differences are reinforced in almost every facet of everyday life. As Walby argues `Training in one or the other set of gender attributes is considered to start from birth in every aspect of their lives` (Walby, 1990: 91). Many individuals within society have accepted that these roles are the `norm` and do not find this problematic, and thus see no requirement to challenge the status quo. Hence we see gender reinforcement in the home, work, education, the media, advertising, entertainment, music, sport and indeed in almost every avenue to which we turn. It is therefore difficult to simply categorise these influences as overt or covert, as many of the influences act on both levels when thoroughly critiqued. Indeed it is not until one gains an awareness of these influences that one can begin to distinguish when, where and how they occur. Thus it can be, and is, argued that `gender is constructed; that is, who we are is shaped by historical circumstances and social discourses, and not primarily by random biology. Gender roles … are constructed from a complex web of influences; some of these effects we control, others we do not` (Berger et al., 1995: 2). Unfortunately the roles prescribed to these genders are not only unfairly assigned upon an unrealistic binary system of gender, they are attributed very unequal values within society. This unfair treatment, it can be argued is one of the forces that constitutes and maintains sexism within society, `The primary engines of sexism … are veiled, subconscious forces. The dominant culture promulgates sexist stereotypes that pervade television, movie, books and music` (LaFollette, 1992: 60). The unfairness of this inaccurate binary system is made clear by an appreciation of the work of Bernard. `In a study of college students Larry Bernard (1980) found only about 35% of males to behave with entirely “masculine” attributes and about 41% of females as consistently displaying “feminine” traits. About one-fourth of both male and female students scored high on both masculine and feminine attributes` (Macionis, 1987, p. 320). This would not only appear to confirm a differentiation between sex and gender, but challenges the whole binary structure with which gender is customarily attributed. Sociological

Reinforcement of Gender and Development of Self As we have discussed, sociological and cultural values and attitudes play a significant role in the development of identity within individuals. This is especially true of the gender identity of each individual. Put succinctly `the self is a social creation, formed in interaction with others but dependent upon and resistant to social meanings attached to the body` Gagné and Tewksbury, 1999: 61). This again would perhaps not be particularly problematic but for three points: · The majority of individuals within society do not readily differentiate between the labels of sex and gender; · Masculinity is often defined as that which is not feminine; · There is a strong value judgement inextricably attached to the traits of femininity and masculinity, that of weakness for the former and strength for the latter. In fact this can be drawn from the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), which defines masculine as manly, virile, vigorous and powerful, whilst describing feminine as womanish and effeminate (LaFollette, 1992: 43). Franklin believes that `for all social actors, gender identity is subject to power relations and normative prescriptions of how one should present oneself`. He goes on to discuss the problems many men face with self-concept because of these normative prescriptions and power relations. Ultimately a man who appears to be lacking in the predefined traits of masculinity, he informs us, may question himself as to whether he is gay, or indeed as to whether he is a man at all (Franklin, 1998). This problem is not confined to men within society. `Throughout our lives, we experience social pressure to conform to gender roles. An assertive young girl who loves competitive sport more than dresses and dolls may be tolerated as a “tomboy”, but in later life ... labelled more negatively as “hard” and “mannish”` (Macionis, 1987: 321). Thus we can see that a varying degree of cognitive dissonance is attached to many everyday actions which these engendered individuals perform. If a girl really wants to play competitive sport, she must overcome male and female pressure to conform to her gender’s norms. Moreover she may begin to question herself to what she really thinks and really wants. Soon there may start to be incongruence between how she feels and how she behaves. This can cause minor or major psychological difficulties for this individual. This is just one example of conforming to society and group norms, however there are many other examples for both male and female stereotypes. How socially acceptable is it for a man to become a `househusband`, for a woman to return to work immediately after giving birth, or for a young boy to aspire to become a hair stylist without being challenged about his sexual preferences? Perhaps one of the most difficult situations individuals may find themselves in is when exploring their sexuality they feel sexual attraction to the same sex. In many areas of our society homosexuality is not generally approved as an acceptable life choice. Unlike other discriminated and oppressed groups homosexuals have an option to `closet` their feelings and behaviours to the outside world, and indeed due to the patriarchal heterosexual significance of masculinity are under much pressure to do so. Berger et al. suggest that `gender identity can act as a coercive ideal that exists principally to protect the norm of heterosexuality` (Berger et al., 1995: 4). Although this alternative may initially seem an easy option, it is easy to underestimate the psychological effects of this incongruence of identity. In extreme cases, this incongruence may see gay men may beat other men for being gay, it is difficult if not impossible to gain an empathic understanding of how this must make them feel. Implications

For Youth Work One of the major implications of gender roles within youth work is the issue of youth being targeted as problematic or at risk, depending almost entirely on their sex. Weitzman has discussed how boys experience more punishment than girls. He describes youth as a time when boys are more closely restricted in their behaviour and are punished for not adhering to traditional male behaviour patterns (Weitzman, 1979). The gender role socialisation of boys is often characterised by negative prescriptions: `don’t be a girl’, `don’t be a sissy`, i.e. do not engage in feminine behaviour. Boys push themselves to be masculine and thus they bury their sensitivities (Jourard, 1968, quoted in Harris, 1995: 43). The difficulty in learning from negative structures rather than positive models can lead to a great deal of stress amongst young males (Harris, 1995: 43). Paradoxically in an attempt to assert overtly masculine characteristics, young men often become perceived as troublesome and problematic. Consequently much youth provision is targeted towards young males. Similarly other caring professions find themselves working within constraints which define which gender will access which service, or be referred to each agency. Much mainstream provision is targeted at young males. This could be due to the `widely held beliefs … that conduct disorders are far more common in boys than girls` (Kerfoot and Butler, 1998: 58). It may be because they are viewed as a) more problematic, and perhaps more importantly b) more threatening. It could be due to the difficulty males have in exploring their individual masculine identities. Or perhaps it is a combination of all of these factors. Whatever the reasons behind it Griffin concurs with the view, explaining that `social welfare provision is also finely graded according to `race` and ethnicity, as well as gender, from a baseline of relatively greater provision for young white males` (Griffin, 1997: 23). It is not just in the realms of academic theory that statistics show greater provision and referral for young males. The Thompson report highlighted the fact that within mainstream youth provision `As regards … young people aged 14 and over, the evidence suggests that … the boys outnumbered the girls by about 3:2`. It goes on to explain that `in terms of their participation in activities and the use of facilities, the boys are more conspicuous than this proportion would suggest` (HMSO, 1982: 63). Davies emphasises the point more clearly, stating that `even a progressive perspective on work with girls still largely saw them as individuals who, though having many unrealised personal talents, were destined to play a range of ‘given’ gender roles` (Davies, 1999: 163). Indeed within my own work in generic youth club settings, in all but one local youth club, I have observed males to outnumber females by at least 2:1. Within the organisation with which I spent an eleven week placement I discovered that although the organisation’s `overall ratio of male:female users is very even, with a slight male bias … the referral waiting list … is predominantly (75%) male` (1st Stage Fieldwork Report). Thus, it can be observed that there is a unmet need for a potential forum for young people, to explore their own identities, without the reinforcement of the negative stereotypes which society has attached to gender. This scope for development is where youth work may play a principal role. For within this multi-faceted, voluntary and developmental realm driven by the needs of young people, individuals may hope to explore, challenge and construct their own identities with minimal interference from those who seek only to control them. Conclusion The issues of gender within individual identity are many and complex, and this is often an oversimplified topic. Gender is learnt by individuals, from birth to death, through society’s values, attitudes and accepted norms. Gender difference, based purely on biological categorisation of male and female is reinforced throughout British society. It is therefore difficult to separate influence on gender into categories of overt and covert influence and reinforcement. However it is important that we recognise this influence in its many forms and guises, and that we analyse and critique its application and effects. Perhaps if we are to make a real difference in the lives of young people we must offer an alternative model of gender. We may offer a model where gender is viewed as a continuum, rather than a binary system. A model in which masculinity is no longer seen as anything which is the opposite of feminine. A model in which attributes prescribed to masculinity and the traits of femininity are equally valued. If we offer this alternative, alongside the core values of equality of opportunity and an acceptance of difference, then we offer young people a valuable opportunity to explore their `selves` and a chance to practice being who they really are. © Student Youth Work Online 1999-2001 Please always reference the author of this page. |

|

References & Recommended Reading |

|

Abbott,

P. and Wallace, C. (1990) An

Introduction To Sociology, Feminist Perspectives Great Britain:

Routledge Abercrombie,

N. and Warde, A. et al (1994) Contemporary

British Society Great Britain: Polity Press Berger,

M., Wallis, B. and Watson, S. (1995) Constructing

Masculinity New York: Routledge Bly,

R. Iron John Reading MA:

Addison-Wesley Davies,

B. (1999) From Voluntaryism to Welfare

State – A History of the Youth Service in England Volume 1. 1939-1979

Leicester: Youth Work Press Franklin,

C. W. Men and Society Chicago:

Nelson-Hall Gagné,

P. and Tewksbury, R. (1999) `Knowledge and

Power, Body and Self: An Analysis of Knowledge Systems and Transgendered Self`

The Sociological Quarterly

Volume 40. No. 1 Griffin, C. (1997) `Representations of the Young` Ch. 2 in Roche, J. and Tucker, S.

(Eds.) Youth in Society Great

Britain: Sage Harris,

I. M. (1995) Messages Men Hear –

Constructing Masculinities London: Taylor and Francis HMSO (1982) Experience

and Participation: Report of the Review Group on the Youth Service in England

(The Thompson Report) Hood-Williams, J. (1996) `Goodbye to Sex & Gender` in Sociological Review Vol. 44, No. 1. Kerfoot,

M. and Butler, A. (1988) Problems of

Childhood and Adolescence London: Macmillan Press LaFollette,

H. (1992) `Real Men` Chapter 4. In

May, L. and Strikwerda, R. (Eds.) Rethinking

Masculinity: Philosophical Explorations in Light of Feminism Boston:

Littlefield Adams Lewis, C. (1986) `Early sex-role socialisation` in Hargreaves, D. J. and Colley, A. M.

(Eds.) The Psychology

of Sex Roles London: Harper and Row Oakley,

A. (1972) Sex, Gender and Society

London: Maurice Temple Smith Oakley,

A. (1981) Subject Women

Oxford: Martin Robertson Oakley, A. (1985) Sex, Gender and Society,

Revised Edition Hampshire: Arena, Gower Ross, H. S. and Goldman, D.

B. (1977) `Infants sociability towards

strangers` Child Development 48,

p. 638-642 Siann, G. (1994) Gender, Sex and Sexuality Bristol: Taylor and Francis Spelke, E.,

Zelazo, P., Kagan, J. and Kotelchuck, M. (1973) `Father

interaction and separation protest`

Developmental Psychology 9, p. 83-90 Walby, S. (1990) Theorising Patriarchy Oxford: Blackwell Weitzman, L. J. (1979) Sex Role Socialization Palo Alto, CA: Mayfield Publishing |

|

Site Links |